Again, this is a much longer post then I'd usually expect to write but I'm just working up a list of topics at the moment and using some material already previously written is given me some time to work on them. This was a response for a unit I'm studying on Media and Society. It examines some sociological perspectives apparent in The Matrix film series (1999-2003). When I first saw the original Matrix film as a kid, I must have watched it at least once a week when it first came out on video. It was the movie for me where I would quote every line even though it took me until my tenth viewing to completely understand the plot (I was 9 at the time).

I was twelve years old when the sequels were released. I recall I was definitely disappointed by them. In Reloaded I felt as if I had sat through two hours of repetitive action stunts with only the promise of the resolution of the gaping plot holes to keep me interested. But by the end, I felt as if absolutely no questions had been answered by the confusing 'Architect' character. I viewed Revolutions as a similarly muddled premise and as a result, never watched either again, and resolved that the franchise had been spoiled by high expectations and over exposure to the masses.

However, I gained a new lease on the franchise this year when I studied it as a topic of media and society. As a mature viewer, I was able to understand the complex mythology developed in the film and appreciate the series as a dense pastiche of a variety of texts from different genres and positions. Anyway, I hope my formal response can convey the new found excitement I found for the franchise and convince any viewers who have been disillusioned with the complex plot to persevere and ultimately reward themselves with a fine cinematic adventure. However, I will caution that it wasn't until I could fully understand a majority of the philosophies and traditions that the Wachowski brothers were influenced by that I could completely appreciate and comprehend the narrative. Perhaps the Wachowski brothers are asking a bit too much of their audiences if they expect them to be knowledgeable of topics as wide ranging as eastern spiritualism to Rene Descartes when they're only showing up to watch mind-blowing actions stunts and breathtaking special effects.

Social Difference and Social Inequality in The Matrix Film Series

The Wachowski brothers’ film series

The Matrix (1999-2003) are a

collection of texts infused with sociological theory and ideology. This sociological

underpinning is depicted very early in the film when the main protagonist Neo

retrieves pirated software from a hollowed out copy of Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation. As an

anecdotal sidenote, the treatise was mandatory reading for members of the cast

in the original film, suggesting the Wachowski’s believed its themes to be

fundamental in understanding the plot. However, the allusions to sociology and

philosophy do not stop there. An underlying theme of The Matrix franchise is the questioning of the nature of reality

and what the audience perceives to be ‘the truth’ in a ubiquitously mediated

world. Therefore, The Matrix draws

from sources such as Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, Calderon de la Barca’s Life is a Dream, Rene Descartes’ evil

genius, Zhuangzi’s butterfly dream and the brain in a vat thought experiment.

Plato's Allegory of the Cave, where the Prisoners accept the nature of their reality (i.e. the shadows) because they have never experienced anything else.

Perhaps of most sociological

significance in the film though is the concept of social difference and social

inequality. This is most clearly portrayed in the conflict of man against

machine. Although this conflict does not directly correlate to any well known

social difference, it provides a symbolic background for exploring issues of

social inequality and cultural clashes. The plot of The Matrix draws on a well established science fiction motif that

the future of man will be shadowed by the fruits of our intellect in the form

of artificially intelligent machines. Through the depiction of this conflict,

the Wachowski brothers were able to introduce notions of social difference and

social inequality. The machines, through their appearance, language, ideology and

pervasive nature represent a monolithic core in a world that isn’t just

ubiquitously occupied by the media, but rather, arguably is the media. In contrast, the humans represent a peripheral

multiplicity of views, ethnicities and beliefs whose existence is constantly

threatened by the monotheistic presence of the machines. Ultimately, these

themes of social difference and social inequality could be interpreted as

encapsulated by the film series central and fundamental theoretical debate of

free will versus determinism.

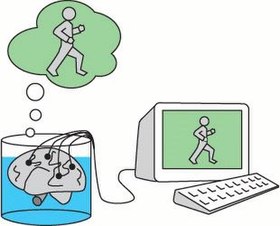

Brain in the vat thought experiment. Similar to Plato's allegory, the mind accepts the nature of it's reality which is indeed the premise and one of the central conflicts of the film series.

The

Core-Periphery Model

The social difference and social

inequality apparent in The Matrix

film series is arguably framed by the core-periphery model. The core-periphery

model was initially an economic theory however it can be translated as a

sociological phenomenon and used to explain the operation of social differences

and inequalities in particular cultures. This theory is said to operate when

one race, ethnicity or religion becomes the most dominant in any given society

for no intrinsic reason. The core is perceived as ‘natural’ or the way the

world is supposed to be. In opposition the periphery can be perceived as

cultures, traditions or beliefs which are seen to be foreign or ‘other’ whose

existence is constantly made to feel insecure by the core. In the film series,

the machines and their agents represent the core social and cultural group. The

machines status as the core can be attributed to their dominance over the

humans. Additionally, and perhaps more symbolically the machines core status

could arguably be a result of the fact that Neo accepts their ideology or their

formulation of reality at the start of the film but is swayed to the periphery

later. Significantly, the machines’ matrix program represents the viewer’s

accepted reality ensuring the levels of indoctrination are multi-layered. In

opposition, the ‘unplugged’ human society represents the peripheral group. In

the film series, the humans are usually depicted as drastically outnumbered and

to be literally surviving on the fringes. Additionally, their appearance and

views represent different ideologies and ethnicities that are typically

peripheral in Western cultures. However, these distinctions will be explained

in greater depth below. What is clear is that the Wachowski’s films can be

analysed following a core-periphery model in the illumination of issues of

social inequality and social difference.

Social

Difference: Appearance

In The Matrix film series, the machines are usually visually

represented in the matrix program by the ever present Agents. Morpheus reveals

to Neo that Agents are effectively free to move in and out of the matrix’s

programming and are essentially the gatekeepers of the system. Significantly,

Agents are portrayed as stereotypical and non-descript middle-aged white men

with no defining physical characteristics. Or as Morpheus pronounces

insightfully, ‘They are everyone, and they are no one’. Indeed, Agents could

just as easily be identified as corporate executives or governmental

operatives, but always someone of an authoritative rank. One of the Agents’

unique skills is their ability to ‘overwrite’ a human ‘plugged into’ the matrix

and thus gain possession of their avatar. The pervasive nature of the Agents is

therefore a subtle nod on behalf of the Wachowski brothers to reveal the core

identity of the machines. Their values and appearances can be superimposed and

thrust upon others regardless of their consent. Due to the machine’s actual

domination, they can dominate the mental space of the subscribers to the

matrix. This itself is an argument formulated by the Marxist school regarding

the mental means of production and ownership over the media. Marxist’s argue

that the bourgeoisie’s dominance is reliant on the fact that they control the

means of mental production (Marx and Engels 1846). The Matrix franchise reinforces this very purposefully through the

authoritative and distinctly bourgeois appearance of the Agents. In opposition,

humans that have been liberated from the matrix are of mixed race, gender and

age. As the film series progresses, it becomes increasingly apparent that the

humans that occupy Zion (a relatively obvious Biblical reference to the human

refuge) represent a far more multi-cultural society then is depicted in the

sanitised world of the matrix, and as a result are far more harmonious.

Therefore, issues of race, gender and age are very clearly portrayed as obvious

social differences and inequalities in The

Matrix film series. While physical appearance is a relatively stark

difference portrayed in the franchise, differences in language between the two

groups becomes an increasingly relevant inequality with great significance.

The Agents possess a uniquely similar appearance.

Social

Difference: Language

The differences between the core

and periphery groups’ language is also a telling feature of social difference

and social inequality. Two aspects in particular of the machines' language

reveals their monolithic and singular thinking presence. When the machine’s

converse in the matrix program, they use as little language as possible and

speak mainly in monosyllabic blocks, particularly the Agents. Additionally,

they refer to elements of the matrix according to their program specific terms

such as ‘the exile’ to refer to deleted programs or ‘the anomaly’ to refer to

Neo. This is eventually taken to its extreme and personified by the Architect

(the father of the matrix program) in The

Matrix Revolutions (2003). The Architect’s language is extremely mechanical

and often reflects the fact that he is the machine which designed the matrix

and thus wrote the complex computer code. He converses in extensive logical

chains of reasoning and frequently employs discourse markers such as ‘ergo’ and

‘concordantly’, and his tone of voice remains constantly level. The formulaic language

structure is compounded by the machines’ singular method of ‘thought-sharing’.

In the film series, it is apparent that machines in the matrix, particularly

Agents, can share each other’s thoughts and seemingly communicate in a

‘hive-mind’ context, as is evidenced by their earpieces. Again, this reinforces

the message that the machines, as the core group possess dominance over the

ideological patterns of the matrix. So pervasive is their rendering of reality

that they are able to share thoughts and react as if a single entity. This is

clearly an example of social difference and social inequality operating within

the film series. It could be construed as a subtle representation of the fact

that the media can be controlled by a group of singular minded ‘robots’ whose

thoughts can hijack the wider community in order to impose their core values

upon the public. The human language in comparison is obviously far more

idiosyncratic and unique. Neo’s constant defiance of the programming language

is displayed by his rejection of the name he was called whilst connected to the

matrix. It is also evidence of the symbolic resistance to the social inequality

dictated by the machines. A concept related closely to that of language is

ideology. While there is a clear social difference in language between the two

groups, this becomes even more apparent in the dichotomy between their

respective ideologies.

The most intellectually challenging scene from the Matrix film series as far as I was concerned, here you can observe the speech patterns employed by the Architect.

Social

Difference: Ideology

As stated above, the machines ideology

is ultimately singular in nature. Throughout the film series, the machines

subscribe to a slavish devotion to belief in the language and ideology of the

matrix programming. For the machines, there is but one belief and that is their

dominance and their perception of the world according to their digital

parameters. While arguably according to the films plot the humans have only one

belief systems themselves, its influences are exceedingly varied. The human’s

belief in Neo as ‘the One’ ironically incorporates a dense amalgamation of

ideologies, spiritualities and beliefs. The human belief system contains

elements of Buddhist, Vedanta, and Advaita Hinduism philosophy, the mythology

of Christianity, Gnosticism, Judaism and Messianism. There are even disparate

elements of existentialism and nihilistic beliefs despite the spiritual

background. This combination of both Eastern and Western belief systems

operates as a perfect metaphor for the peripheral groups in the film series.

The marginalisation demonstrates how social inequality and social difference

can operate in marginalising religions and ideologies. Indeed, the machines

impose an almost atheistic belief system upon the humans whilst connected into

the matrix. Or as Agent Smith suggests in the original film, an incongruous

belief in the superiority of mankind due to technological advances which have

in fact been created as a control system by the machines. This lead to the

nihilistic beliefs Neo experiences at the start of the film in which he

constantly questions the nature of reality. However, once liberated, Neo is

exposed to the prophetic teachings of the Oracle and Morpheus which encourage a

wider belief system. However, the central conflict of the film represented by

all the social differences outlined above are essentially crystallised in the

depiction of free will versus determinism that is a constant theme throughout

the franchise.

Free

Will vs. Determinism

The central conflict of the film

series arises from a belief in determinism over free will. This antagonism

represents the culmination of the social inequalities and differences depicted

throughout the films. Neo and the humans represent free will, hence Neo’s

spiritual transcendence as ‘the One’. Neo represents individuality,

idiosyncrasy and most importantly, choice. Agent Smith and the machines in

comparison are the physical manifestations of determinism or pre-ordained fate

represented by an identical and therefore homogeneous community. Paradoxically,

Neo as ‘the One’ represents many unique voices. However, Agent Smith as a virus

that is able to copy himself infinitely becomes ‘the Many’ but a representative

of only one ideology and one way of life (that is, the machines autocracy).

This serves as a very complex metaphor for social difference and social

inequality. The Wachowski brothers’ message could be construed as an attempt at

indicating that in a wholly mediated world such as the matrix (which is the

audience’s reality) there is always the temptation to accept without question

the nature of our world and subscribe to the pervasive beliefs of those in

authority. However, Neo’s defiance and his ability to chose alternative options

despite what may seem inevitable, represents the peripheral voices of society

willing to question the established norms and provide alternative opinions in

the media.

The One vs. The Many, personifying the central theoretical conflict of the film.

Therefore, the Wachowski brothers Matrix franchise is arguably an accurate

and thought provoking representation of the media in contemporary society. The

films’ characters and antithetical narrative symbolises the social differences

and inequalities regarding race, class and ideology experienced by core and

periphery groups. The ultimate conclusion of the film suggests that this

antagonism can only be resolved once the two cultures are harmoniously combined

as are Agent Smith and Neo. The Matrix

franchise’s relevance to media studies is hardly surprising given its eclectic

and intelligent combination of influences ranging from philosophy to comic

books. Not only do The Matrix films

reflect what a Mediapolis would look like (Deuze 2011, 137), it is itself a

highly mediated and self-aware product that constantly challenges the audience

to question the nature of their reality and the social differences and

inequalities that are increasingly apparent in an over-mediated world.

References

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1846) The German Ideology.

Wachowski, Larry and Andy. (1999) The Matrix, Motion picture, Sydney:

Village Roadshow Pictures.

Wachowski, Larry and Andy. (2003) The Matrix: Reloaded, Motion picture,

Sydney: Village Roadshow Pictures.

Wachowski, Larry and Andy. (2003) The Matrix: Revolutions, Motion picture,

Sydney: Village Roadshow Pictures.

This uni must find a reason to watch the Matrix in all courses because I too watched it as part of my education degree.

ReplyDeleteThe question for the assignment was how does social inequality operate within a science fiction text. So we had to chose a science fiction film we thought would suit the assignment and I chose the Matrix myself. But it is a strong enough text that I'm sure it could fit the content of many courses!

DeleteHello, this is a nicely explained article. Your piece was very informative. I had never heard the issue presented in that light. Thanks for your hard work.

ReplyDeletewalk production

social media marketing agency

design agency kl